"It

is impossible to find your way among the manoeuvres of the leaders,

without searching out the deep molecular processes in the mind of the

masses. In July the workers and soldiers were defeated, but in October …

they seized the power. What happened in their heads during those four

months?"

|

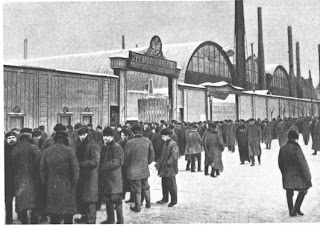

| The Putilov Factory |

Weathering the storm

“The immediate causes of the events of a revolution are changes in the states of mind of the conflicting classes. The material relations of society merely define the channel within which these processes take place. Changes in the collective consciousness have naturally a semi-concealed character. Only when they have attained a certain degree of intensity do the new moods and ideas break to the surface in the form of mass activities which establish a new, although again very unstable, social equilibrium. It is impossible to find your way among the manoeuvres of the leaders, without searching out the deep molecular processes in the mind of the masses. In July the workers and soldiers were defeated, but in October … they seized the power. What happened in their heads during those four months? Here the reader will find it necessary to go back to the July defeat. It is often necessary to step back a few paces in order to make a good leap. And before us is the October leap” (88).

“In the official Soviet histories the opinion has become established … that the July attack upon the party went by almost without leaving a trace upon the workers’ organisations. That is utterly untrue. The decline … did not, to be sure, last very long – not longer than a few weeks ... but the defeat of the workers and soldiers of the capital was … bound to produce an enormous impression. Fright, disappointment, apathy, flowed down differently in different parts of the country, but they were to be observed everywhere” (89).

In Petrograd, the right-wing gangs didn’t just set upon Bolshevik offices, they also targeted buildings belonging to the unions and district soviets, even the Mensheviks. Passers-by simply looking like workers or suspected of being Bolsheviks could be beaten up without warning.

Immediately after the July Days, the members of the Bolsheviks’ leading bodies retreated to the Vyborg district. Their printing plants had been destroyed and for several weeks no printer would risk producing their material. The party’s activities became semi-legal and so the Bolsheviks relied on their work in the unions and factory committees. In the political arena, only Martov and his group at the extreme left of the Mensheviks spoke up for the revolution.

The July events hit the Petrograd garrison particularly hard. The soldiers had been quickest to come out onto the streets but also now retreated the furthest. “It was exactly in those most revolutionary regiments which had marched in the front rank in the July Days, and therefore received the most furious blows, that the influence of the party fell lowest. The Military Organisation was compelled to draw in very decidedly. In Kronstadt the party lost about 250 members” (90).

Events went the same way in Moscow and, with some exceptions to the rule, worse again in the provinces. One worker reported how he attended a meeting of a Moscow district soviet soon after the July Days: “I saw there were none too many of our comrade Bolsheviks … Steklov, one of the energetic comrades came right up close to me and … asked, ‘Is it true they brought Lenin and Zinoviev in a sealed train? Is it true they are working on German money?’ My heart sank ...” (91).

Reports from the region around Moscow described distinct hostility to the party with speakers even being beaten up. The Bolsheviks were forced to withdraw not only from the soviets but even from trade union work in these areas.

Membership fell off rapidly and in some of the southern provinces there was no remaining party organisation at all. In Kiev the Bolsheviks recorded a mere 6% of votes in elections to the local duma and the party paper had to go back from daily to weekly production.

“The disbandment and transfer of the more revolutionary regiments must in itself not only have lowered the political level of the garrisons, but also grievously affected the local workers, who felt firmer when friendly troops were standing behind their backs”. (92).

As might have been expected, the reaction at the front was particularly fierce. Special reactionary units of ‘Duty to the Free Fatherland’ were set up and used alongside the Cossacks to help root out Bolshevik agitators.

However, while the officers’ oppression might have frightened the troops for a while, it could not win their support. While, on the surface, there appeared to be some restoration of the previous army discipline, underneath a burning hatred for the officers was developing. “If the soldiers had become more restrained, it was only because they had learned to a certain extent to discipline their hatred; when the dams broke their feelings were only the more clearly revealed” (93).

“The political development of the masses proceeds not in a direct line, but a complicated curve. Objective conditions were powerfully impelling the workers, soldiers and peasants toward the banner of the Bolsheviks, but the masses were entering upon this path in a state of struggle with their own past. At a difficult turn … the old prejudices not yet burnt out would flare up” (94).

“The … acuteness of the reaction to this partial defeat was in some sense a payment made by the workers, and yet more the soldiers, for their too smooth … flow to the Bolsheviks during the preceding months. This sharp turn … produced an automatic … selection within the cadres of the party. Those who did not tremble in those days could be relied on absolutely in what was to come. On the eve of October in … allotting tasks, the organisers would glance round … calling to mind who bore himself how in the July Days” (95).

“The July reaction established a kind of decisive watershed between the February and October revolutions. The blow was in reality psychological rather than physical, but it was no less real for that. During the first four months all the mass processes had moved in one direction – to the left. Now … this inner crisis in the mass consciousness … caused confusion and retreat. These receding waves in the flood of revolution developed an overwhelming force. You cannot conquer such a wave head on. Hold out until the wave of reaction has exhausted itself, preparing in the meantime points of support for a new advance” (96).

The Bolshevik Congress

The Bolsheviks had always had an influence out of all proportion to the meagre resources at their disposal. They lacked speakers, particularly to build the party outside Petrograd itself. The party’s various publications had had a total circulation of only 320,000 up to the July Days. Now, this was cut by half.

The limited circulation of the party press had always been countered by the Bolsheviks having ideas and slogans that corresponded to the needs and moods of the moment. So each paper was read and shared around the factories and barracks – while the bourgeois papers freely supplied to the front remained unopened or, as one Division reported, burned to boil the water for tea!

“The agitation of the Bolsheviks was distinguished by its concentrated and well-thought-out character … a continual analysis of the objective situation, a testing of slogans upon facts, a serious attitude to the enemy even when he was none too serious” (97).

After the July Days, just such a serious analysis was vital. So, in spite of all difficulties, the planned Sixth Congress of the Bolshevik Party went ahead from July 26th, its sessions concealed in two different workers’ districts.

The congress was officially a joint congress planned to bring about the inclusion of various independent groups into the Bolsheviks. Most important of these was the ‘Mezhrayontsi’, the Petrograd inter-district organisation that Trotsky, Lunacharsky, Joffé and other revolutionaries belonged to.

“It was only at this July congress that Trotsky formally joined the Bolshevik Party. The balance here was struck to years of disagreement and factional struggle. Trotsky came to Lenin as to a teacher whose power and significance he understood later than many others, but perhaps more fully than they” (98).

There were 175 delegates representing 112 organisations and 176,750 members in all. There were 36,000 Bolsheviks in Petrograd plus the 4,000 Mezhrayontsi and 1,000 in the Military Organisation. The Party had 42,000 members in the industrial regions around Moscow, 25,000 in the Urals, 15,000 in the Donetz basin and significant numbers in some of the main cities of the Caucasus.

Lenin, Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev received most votes in the elections for the Central Committee although Trotsky was now in prison and the other three could not risk attending the congress. Nevertheless, Lenin’s theses formed the basis of the discussions. Unlike April, the unity of the meeting was noticeable.

The Congress confirmed the party’s warnings against being drawn into premature conflicts but also explained the need to prepare for an armed insurrection. In doing so, the congress withdrew the central slogan of the previous period – “All Power to the Soviets”. Before the July Days, a peaceful transfer of power to the soviets, followed by the winning of a Bolshevik majority within them, had seemed possible - but no longer.

“If the Executive Committee should now have decided to introduce a resolution transferring the power into its own hands, the result would have been wholly different from … before. A Cossack regiment … would probably have entered the Tauride Palace … to arrest the ‘usurpers’. The slogan ‘Power to the Soviets’ from now on meant armed insurrection against the government and those military cliques which stood behind it. But to raise an insurrection in the cause of ‘Power to the Soviets’ when the soviets did not want [it], was obvious nonsense” (99).

The new demand would now have to be: “The candid slogan of the conquest of power by the proletariat and the peasant poor. This was not a renunciation of the soviets as such. After winning the power, the proletariat would have to organise the state upon the soviet type. But these would be other soviets … directly opposite to the defensive function of the Compromisist soviets” (100).

The Masses Recover

The industrialists had sought to take advantage of the workers’ weakness in July by going on the offensive. A key part of their strategy had been deliberate economic sabotage, closing down factories, concealing raw materials, even deliberately flooding mines and destroying machinery. But the workers had responded with a wave of strikes. While the more experienced layers held back, fresher workers like those in the textile, leather and paper industries came to the fore.

As time went on, the slander against the Bolsheviks began to lose its effect in the factories. After all, it was hard to believe your workmate was a German spy when you had known him for years. It had only taken days for the most politically advanced workplaces in Petrograd to recover. They started to mount protests against the arrests and slanders.

By the end of July, the Bolsheviks had regained their position in Petrograd’s factories and were again able to carry out agitational work in the city. Slutsky, Volodarsky and Yefdokimov toured meetings around Petrograd. The 50,000-strong ‘Union of Youth’ was also coming under increasing Bolshevik influence.

Even the soldiers soon began to wonder, as Trotsky puts it: “If the Bolsheviks are German spies, why does the news come chiefly from sources most hateful to the people … the Kadet press? Why in accusing ‘Lenin & Co.’ do they shake their fists in the very faces of soldiers, as though they were the traitors?” (101)

Then, on July 21st and 22nd, just as the Compromisers and bourgeoisie were wrangling over their new coalition, a far more significant coalition began to form – between the workers and soldiers.

Delegates from the front had been arriving in the capital to try and meet with the Soviet E.C. to protest at the restoration of the old regime’s methods at the front. But the E.C. refused to meet them. Instead, encouraged by the Bolsheviks, the delegates went to discuss with the workers and soldiers of Petrograd. These discussions then led to a conference being called from below with representatives from 29 regiments at the front, 90 from Petrograd factories plus delegations from the Kronstadt sailors and other surrounding garrisons.

“The Petersburg workers listened to the men from the front eagerly. Those grey soldiers … painted in unstudied words … how everything was crawling back to the old, hateful … regime. The contrast between the hopes of yesterday and today’s reality struck home to every man there. A Bolshevik resolution was passed almost unanimously. The dispersing delegates will tell the truth about how the Compromise leaders repulsed them and the workers received them. And the trenches will believe their delegates” (102).

These meetings with the representatives from the front helped the Petrograd garrison recover, although some of the regiments most to the fore in July still retained their caution and apathy. The Bolshevik Military Organisation started to get back on its feet, helped by the involvement of Sverdlov and Dzerzhinsky from the Central Committee.

The party also began to recover in Kronstadt and amongst the sailors based at Helsingfors. By August, a Bolshevik, Brekman, was elected president of the Kronstadt soviet. “The sailors had been to a considerable degree the instigators of the July movement, acting over the head of, and to an extent against the will of the party. The experience … had shown them that the question of power is not so easily solved. Semi-anarchistic moods had now given place to confidence in the party” (103).

After some delay, Moscow began to take the same road as Petrograd, as soon became clear in the strength of the strike against the State Conference. Events at the Conference itself further accelerated the leftward move of the masses and the growth of the Bolsheviks.

The leftward shift of Petrograd’s Mensheviks was shown when they voted to exclude Tseretelli from their election list for the city duma. Then the city’s Social Revolutionaries voted to dissolve the reactionary League of Officers at headquarters. On August 18th, nearly all of the 900 delegates to the Petrograd Soviet voted to demand the abolition of the death penalty. Only 4 votes were cast against - the leading Compromisers, Tseretelli, Cheidze, Dan and Lieber!

The Petrograd duma elections on August 20th saw the Social Revolutionaries losing votes, although still with the largest share at 37%, with the Kadets winning a fifth of the poll. The Mensheviks receeived only a pitiful 4%. However, to everyone’s surprise, the Bolsheviks won a third of the total poll.

Similar strides forward for the Bolsheviks were demonstrated in elections and conferences right across the country. For example, the party had recovered sufficiently in Kiev to handsomely win a majority at a conference of factory and shop committees held on August 20th.

The Fall and Rise of the Soviets

From February onwards, despite an inevitable lagging behind and sometimes deliberate postponement of elections, the changing fortunes of the parties had been reflected in the make-up of the soviets. With increasing Bolshevik influence, came also an increasing involvement of the soviets in the direct administration and control of local industry, agriculture and justice.

By early July, many provincial soviets, such as those in the Urals, were already in effect organs of power in their localities. This was an anticipation of the soviet organisation following the revolution. The July Days cut right across this development.

While the role of parties and unions still seemed clear even in a time of reaction, in the aftermath of the July Days it was unclear whether the soviets had any future at all. Instead of soviet power, control by the government and its commissars had been strengthened instead. Other functions were being transferred to the factory committees and municipalities.

Indeed, Lenin was coming to the opinion that the compromisist soviets might just wither on the vine and that it would be the Bolshevik-led factory committees that were likely to become the organs of insurrection. After all, the Moscow strike against the State Conference had been called from the factories against the opposition of the Moscow Soviet leaders.

Soviets are revolutionary bodies and, unless being used for the struggle for power, begin to lose their purpose. The Compromise leaders of many of the soviets no longer sought to use their power, giving way to the bureaucracy instead. Many soviets turned into pointless talking shops. Nevertheless, the total number of soviets was still growing, reaching 600 by the end of August, as the idea was still taking hold in more backward counties and regions.

The decline in the fortunes of the Soviet Executive Committee even allowed the government to push the E.C. out of the Tauride Palace into the Smolny Institute.

However, in late July, a revival of the soviets had already started, from the bottom up, as the Bolsheviks began to restore their support in the districts of Petrograd. Their demands at first were limited – against mass arrests, for restoration of the Left press, an end to the disbandment of regiments and the death penalty at the front, for example.

By August, as well as in Kronstadt, the Bolsheviks were winning soviet majorities in a number of areas and more radical slogans were starting to be raised including, once again, the transfer of power to the soviets.

“After the temporary halt in its growth Bolshevism again began confidently spreading its wings. ‘The compensation is coming fast,’ wrote Trotsky in the middle of August. ‘Driven, persecuted, slandered, our party has never grown so swiftly as in recent days. And this process will not be long in running from the capital to the provinces, from the cities into the village and the army. All the toiling masses of the country will have learned, when new trials come, to unite their fate with the fate of our party’ ” (104).

No comments:

Post a Comment